Democrats last prevailed in a Nebraska Senate contest eighteen years ago. Dan Osborn is attempting something new instead of jumping into yet another party-line shellacking.

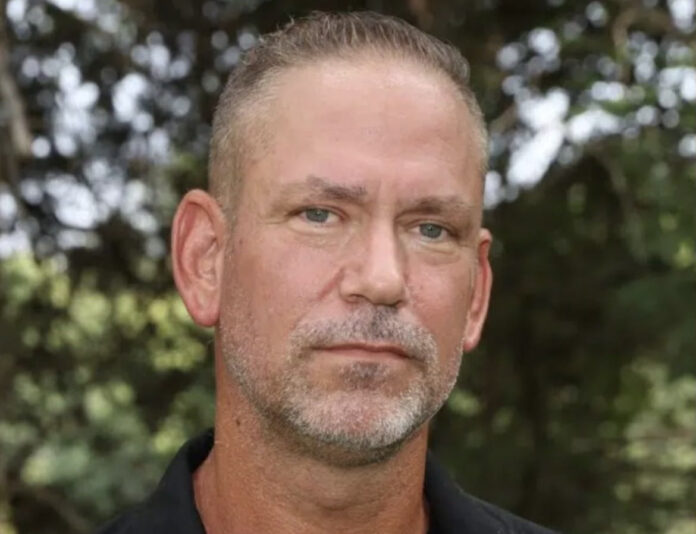

The union boss and steamfitter is an independent candidate for senator, with the implied support of Democrats who choose not to field a rival to Republican Deb Fischer (Neb.). Even if he does win, he has some innovative plans to remain distant from the Democratic Party. He is the third independent in as many elections to seek to unite anti-Republican coalitions in extremely red areas.

As he sipped his beer in between fundraising engagements during his swing in D.C., Osborn stated, “I would like to create an independent caucus” in an interview this week. “I understand that sounds wild.”

Osborn, 49 years old, has tried and failed in other independent races in red states in recent years, so this is definitely a long-shot tactic for him. In 2020, Al Gross surprised Republican Senator Dan Sullivan of Alaska with roughly $20 million in contributions, and in 2022, Evan McMullin presented his independent argument to Republican Senator Mike Lee of Utah.

Both did better than a standard Democratic candidate but were still defeated by wide margins. That’s due in part to the fact that people in both states naturally doubt that they’re truly independent of the Democratic Party.

Osborn stands out from the other candidates due to his populist views. However, his task is comparable to that of previous independents.

“If I were her, I would paint myself as a Democrat in sheep’s clothing,” Fischer says, implying that she plans to do just that. “I’m pro-labor, so I’m sure people will call me a communist,” Osborn warned. This is not who I am, he said, and voters will “realize and understand.”

He has over $600,000 in the bank, but he thinks he needs another $5 million to really compete. He plans to quit his work as a steamfitter and devote himself fully to racing, even though he knows there will be challenges.

Senator Angus King (I-Maine) admitted that it is challenging to run as an independent in a state without a history of such nominations. For an independent, getting people to believe A: You mean business is the biggest challenge. B: That there is hope for you.

With eight years of experience under his belt as governor, King was well-prepared for his 2012 Senate race. It helped King’s ascent because “it made it thinkable that [voters] could vote for an independent again” (as he put it), because Maine had an independent governor in the 1970s.

Nebraska has a somewhat distinct political culture than the rest of the country. It hasn’t had an independent senator since 1936, when George Norris won his last term with a small Democratic majority. In the 88 years that followed, politics underwent significant changes.

Legislator Pete Ricketts (R-Neb.) predicted that Dan would have trouble gaining support.

Fischer is a reliable fundraiser, has excellent relationships to GOP leaders, and never makes a misstep. Fischer has not caused as much controversy inside the Nebraska Republican Party as his predecessor, Ben Sasse (R-Neb.), did.

Osborn has been an independent since 2016, but his Republican views are at odds with his Democratic ones since he supports abortion rights and labor unions. While he “probably wouldn’t” endorse a full impeachment trial for Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, he did voice his support for increasing background checks for gun sales and for removing the legislative filibuster.

However, he is still against banning assault weapons, wants to “close” the border until legislative compromises are reached, and claims he would have voted against the 2021 infrastructure plan, which Fischer supported, due to its impact on the national debt. He expresses his disappointment that the centrist group No Labels was unable to run for president and praises Sen. Ben Sasse, who was critical of former president Trump.

By uniting with Democrats in Nebraska and around the country, Osborn is essentially pledging to work toward a common objective: the removal of a Republican from office. According to him, Democrats in his state are “being supportive” and he has had informal contact with the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, but no official endorsement.

On November’s ballot, you’ll be able to see Ricketts and Fischer, maybe alongside marijuana and abortion referendums. Osborn thinks that these complex ballot patterns may help split party-line votes in November.

Fischer is running for reelection with the support of her own labor group, but Republicans don’t appear to be concerned about Osborn just yet. “Totally out of step with Nebraskans” was how Fischer characterized Osborn in a statement.

He has stated, “I have no idea what farmers or ranchers do,” and he wants to legalize narcotics and favors limitless abortion. “Is he serious about running for senator from Nebraska?” she asked.

As for the unfair treatment of farmers and laborers by the country club U.S. Senate, Osborn said, “No one in Washington understands how this is happening.”

Osborn will require the backing of a sizable portion of Trump’s votes in addition to the support of virtually every Democrat and centrist in the state, as the task of ticket-splitting becomes even more challenging. He stated his intention to cast an independent ballot for president, but he is ill-informed about RFK Jr.’s background to provide an opinion on his campaign.

Until he gets in his car and heads to the polls, he probably won’t have a clue who he wants to lead the nation in the presidency.